Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), and splanchnic vein thrombosis, is a frequent complication of cancer.1 The development of cancer-associated VTE is associated with reduced quality of life and places a significant economic burden on both the patient and the health care system.2 VTE is the second-leading cause of death in cancer outpatients receiving chemotherapy and has been shown to be an independent predictor of mortality in the population of patients with cancer.3,4 The management of cancer-associated VTE treatment can be challenging because the risks of recurrent VTE and anticoagulant-related bleeding are high despite appropriate management.5 In addition, drug interactions and cancer-related comorbidities, such as renal and/or hepatic dysfunction, decreased oral intake, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, and thrombocytopenia also add to treatment complexity by limiting the choice of anticoagulant agent.

Clinical Trials Evaluating Low Molecular Weight Heparin for the Treatment of Cancer-Associated VTE

The long-term use of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) for the treatment of VTE in patients with active cancer is recommended as first-line therapy based on the results of multiple open-label randomized controlled trials (RCTs).6,7 The two largest studies published to date, the CLOT (Comparison of Low-molecular-weight heparin versus Oral anticoagulant Therapy for the Prevention of Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Cancer) and CATCH (Comparison of Acute Treatments in Cancer Haemostasis) trials, compared a LMWH to vitamin K antagonist therapy in patients with active cancer and acute symptomatic proximal DVT or PE. See Table 1 for baseline characteristics and Table 2 for study results.8,9 Both trials used an open-label study design, the same target international normalized ratio (INR) in the vitamin K antagonist control arm, the same active cancer definition, and the same duration of treatment and had comparable patient eligibility criteria.

P Clot Trial Procedure

BACKGROUND:Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a common and important complication of stroke. The CLOTS 3 trial aims to determine whether, compared with best medical care, best medical care plus intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) in immobile stroke patients reduces the risk of proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT). The CLOTS 3 trial aims to determine whether, compared with best medical care, best medical care plus intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) in immobile stroke patients reduces the risk of proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

Original Article Jan 13, 2021 Interim Results of a Phase 1–2a Trial of Ad26.COV2.S Covid-19 Vaccine J. Sadoff and Others More from the week of December 23, 2010. Abstract This case demonstrated a feasible alternative to treat 'clot in transit' associated with pulmonary embolism using FlowTriever Inari device. The pre‐existing approved AngioVac device requir.

Table 1: Study Design and Baseline Characteristics of the CATCH and CLOT Trials

Table 2: Outcomes in the CLOT and CATCH Trials

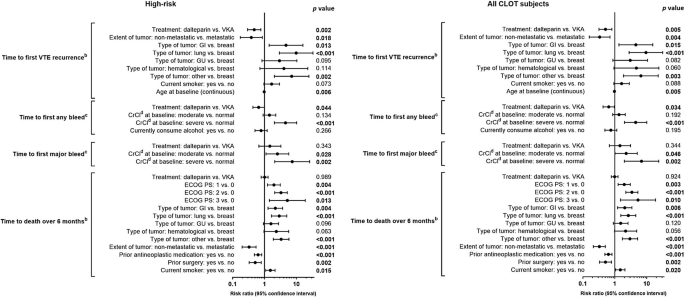

The CLOT trial, published in 2003, randomized 676 patients to receive dalteparin (200 IU/kg daily for 1 month followed by 150 IU/kg daily for 5 months) or vitamin K antagonist (warfarin or acenocoumarol with target INR 2.5 for a total of 6 months with an initial 5-7 days overlap with dalteparin 200 IU/kg).8 Symptomatic recurrent DVT or PE, including death related to PE, was observed in 27 patients (7.0%) randomized to dalteparin and in 53 patients (15%) randomized to vitamin K antagonist (hazard ratio [HR] 0.48; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.30-0.77; p = 0.002). No difference in the rates of major bleeding (6 vs. 4%; p = 0.27), any bleeding (15 vs. 19%; p = 0.09), or death (39 vs. 41%; p = 0.53) were observed between the 2 groups.

In the CATCH trial, published over 10 years later in 2015, 900 patients were randomized to tinzaparin (175 IU/kg daily without dose reduction) or warfarin (target INR 2.0-3.0 with initial tinzaparin 175 IU/kg overlap for 5-10 days) for a total of 6 months.9 The primary composite endpoint of recurrent VTE including incidental proximal DVT and PE occurred in 31 patients (6.9%) in the tinzaparin arm and 45 patients (10%) in the warfarin arm (HR 0.65; 95% CI, 0.41-1.03; p = 0.07). Symptomatic DVT occurred in significantly fewer patients treated with tinzaparin (2.7 vs. 5.3%; HR 0.48; 95% CI, 0.24-0.96; p = 0.04). Although major bleeding rates were similar in both arms, a significant reduction in clinically relevant, non-major bleeding was observed with tinzaparin (10.9 vs. 15.3%; HR 0.58; 95% CI, 0.40-0.84; p = 0.004). Mortality was similar in both groups, with approximately one-third of patients dying during the study period (33.4 vs. 30.6%; p = 0.54). Although tinzaparin did not significantly reduce the primary composite endpoint of recurrent VTE, the CATCH study results do support the use of long-term LMWH as the preferred treatment for cancer-associated VTE due to a lower risk of clinically relevant major bleeding and a significant reduction in recurrent DVT.

The failure of the CATCH trial to meet statistical significance for the primary endpoint may be due to the lower-than-expected recurrent VTE rate observed in the warfarin arm. One possible explanation for this observation could be an improvement in warfarin management in the CATCH trial. However, similar levels of INR control in both studies argue against this (time in therapeutic range was 46% in CLOT vs. 47% in CATCH; time above the therapeutic range was 24% in CLOT vs. 27% in CATCH). A more likely explanation is a bias in the selection of 'less sick' patients for enrollment in the CATCH trial. Although the CATCH and CLOT studies used similar inclusion and exclusion criteria, key differences in baseline characteristics exist between the two patient populations, particularly with respect to thrombotic and prognostic risk factors. A higher proportion of patients in the CLOT trial were receiving active cancer treatment (72% CLOT vs. 53% CATCH), had a history of prior VTE (11% CLOT vs. 6% CATCH), had evidence of metastatic disease (67% CLOT vs. 55% CATCH), and had a poorer performance status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score of 2 in 36% CLOT vs. 23% CATCH). In addition, mortality during the 6-month treatment period was also higher in the CLOT population (39% CLOT vs. 32% CATCH). Thus, the CATCH patient population likely had a lower inherent risk of recurrent VTE compared with CLOT study patients. It is highly probable that investigators did not enroll patients into CATCH if they felt LMWH would be more beneficial than warfarin, resulting in the selective enrollment of patients who were less likely to develop recurrent VTE.

Trials Evaluating Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Cancer-Associated VTE

Patient selection bias is even more evident in the recent randomized trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for treatment of acute VTE.10 These oral anticoagulants have been extensively studied over the last decade in atrial fibrillation, VTE treatment, and VTE prevention. In the landmark phase III clinical trials for acute VTE treatment, it was consistently demonstrated that DOACs are non-inferior to warfarin (pooled relative risk [RR] 0.90; 95% CI, 0.77-1.06) in preventing recurrent VTE, and they have a similar or reduced risk of major bleeding (pooled RR 0.40; 95% CI, 0.45-0.83).11 Among those patients who were classified as having 'cancer' or 'active cancer' in these studies, DOACs also seem to perform similarly to warfarin.12 But a more in-depth examination of these post-hoc data reveals important patient-selection bias and questions the generalizability of the DOAC trial results to 'real life' patients with cancer with VTE. In addition to the heterogeneous definitions of 'active cancer' used in these trials that differed from the CLOT and CATCH trials, important determinants of recurrent VTE and bleeding were also very different in the DOAC patients with cancer from the LMWH cancer-specific trials (Table 3). These include presence of metastatic disease and concomitant use of anticancer therapy. The vast differences in mortality during the study period also argue that very different groups of patients with 'cancer' were included in the DOAC versus LMWH trials. Furthermore, unlike LMWH, which is associated with a significant reduction in risk of recurrent VTE compared with vitamin K antagonists (RR 0.52; 95% CI, 0.36-0.74), DOACs did not significantly reduce this risk in a meta-analysis of 1,132 patients with cancer enrolled in the EINSTEIN clinical trial program, HOKUSAI-VTE (Edoxaban Versus Warfarin for the Treatment of Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism), RECOVER (Efficacy and Safety of Dabigatran Compared to Warfarin for 6-Month Treatment of Acute Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism), and AMPLIFY (Apixaban for the Initial Management of Pulmonary Embolism and Deep-Vein Thrombosis as First-Line Therapy) RCTs (RR 0.66; 95% CI, 0.39-1.11).10 All these considerations should caution the unselected use of DOACs in patients with active cancer and acute, symptomatic VTE.13

Table 3: Study Design and Baseline Characteristics of the Subgroups of Patients With Cancer From the Phase III DOAC Trials

Conclusions

All major evidence-based consensus guidelines recommend LMWH for the initial and long-term treatment of cancer-associated VTE.6,7,13 This recommendation is based on the observation that LMWH not only is more effective than warfarin for the prevention of recurrent VTE, but also offers additional advantages over oral agents including stable anticoagulation in patients with poor oral intake, a lack of drug interactions, and clinical experience in the management of anticoagulation surrounding invasive procedures and thrombocytopenia. Although DOACs are not currently recommended for VTE treatment in patients with cancer, RCTs comparing rivaroxaban and edoxaban to LMWH are currently ongoing and will help to clarify their role in cancer-associated VTE.6,13

References

- Khorana AA, Dalal M, Lin J, Connolly GC. Incidence and predictors of venous thromboembolism (VTE) among ambulatory high-risk cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy in the United States. Cancer 2013;119:648-55.

- Kourlaba G, Relakis J, Mylonas C, et al. The humanistic and economic burden of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: a systematic review. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2015;26:13-31.

- Kuderer NM, Ortel TL, Francis CW. Impact of venous thromboembolism and anticoagulation on cancer and cancer survival. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:4902-11.

- Khorana AA, Francis CW, Culakova E, Kuderer NM, Lyman GH. Thromboembolism is a leading cause of death in cancer patients receiving outpatient chemotherapy. J Thromb Haemost 2007;5:632-4.

- Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Piccioli A, et al. Recurrent venous thromboembolism and bleeding complications during anticoagulant treatment in patients with cancer and venous thrombosis. Blood 2002;100:3484-8.

- Lyman GH, Bohlke K, Khorana AA, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer: american society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline update 2014. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:654-6.

- Streiff MB, Holmstrom B, Ashrani A, et al. Cancer-Associated Venous Thromboembolic Disease, Version 1.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2015;13:1079-95.

- Lee AY, Levine MN, Baker RI, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin versus a coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;349:146-53.

- Lee AY, Kamphuisen PW, Meyer G, et al. Tinzaparin vs Warfarin for Treatment of Acute Venous Thromboembolism in Patients With Active Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2015;314:677-86.

- Carrier M, Cameron C, Delluc A, Castellucci L, Khorana AA, Lee AY. Efficacy and safety of anticoagulant therapy for the treatment of acute cancer-associated thrombosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res 2014;134:1214-9.

- van Es N, Coppens M, Schulman S, Middeldorp S, Büller HR. Direct oral anticoagulants compared with vitamin K antagonists for acute venous thromboembolism: evidence from phase 3 trials. Blood 2014;124:1968-75.

- Vedovati MC, Germini F, Agnelli G, Becattini C. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with VTE and cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 2015;147:475-83.

- Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2016;149:315-52.

- Agnelli G, Büller HR, Cohen A, et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: results from the AMPLIFY trial. J Thromb Haemost 2015;13:2187-91.

- Prins MH, Lensing AW, Brighton TA, et al. Oral rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin with vitamin K antagonist for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer (EINSTEIN-DVT and EINSTEIN-PE): a pooled subgroup analysis of two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Haematol 2014;1:e37-46.

- Raskob GE, van Es N, Segers A, et al. Edoxaban for venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: results from a non-inferiority subgroup analysis of the Hokusai-VTE randomised, double-blind, double-dummy trial. Lancet Haematol 2016;3:e379-87.

- Schulman S, Goldhaber SZ, Kearon C, et al. Treatment with dabigatran or warfarin in patients with venous thromboembolism and cancer. Thromb Haemost 2015;114:150-7.

Clinical Topics:Anticoagulation Management, Arrhythmias and Clinical EP, Cardio-Oncology, Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism, Anticoagulation Management and Atrial Fibrillation, Anticoagulation Management and Venothromboembolism, Atrial Fibrillation/Supraventricular Arrhythmias

Keywords:Cardiotoxins, Cardiotoxicity, Heparin, Low-Molecular-Weight, Warfarin, Anticoagulants, International Normalized Ratio, Acenocoumarol, Dalteparin, Antithrombins, Venous Thromboembolism, Risk Factors, Atrial Fibrillation, Outpatients, Research Personnel, Quality of Life, Pyridones, Pyrazoles, Pyridines, Thiazoles, Venous Thrombosis, Pulmonary Embolism, Thrombosis, Thrombocytopenia, Comorbidity, Hemostasis, Neoplasms

< Back to Listings

< Back to ListingsVisit the News Hub

Large clinical trial concludes such treatment does not prevent long-term complications

Getty ImagesAbout half of people with blood clots in the deep veins of their legs develop a complication that involves chronic limb pain and swelling, making it difficult for some to walk and perform daily activities. A large-scale clinical trial has shown that a risky, costly procedure to remove such clots fails to reduce the likelihood that patients will develop the debilitating complication.

Not all patients with blood clots in their legs – a condition known as deep vein thrombosis – need to receive powerful but risky clot-busting drugs, according to results of a large-scale, multicenter clinical trial.

The study showed that clearing the clot with drugs and specialized devices did not reduce the likelihood that patients would develop post-thrombotic syndrome, a complication that can leave patients with chronic limb pain and swelling, and can lead to difficulty walking or carrying out their daily activities. Use of the potent drugs did, however, raise the chance that a patient would experience a dangerous bleed.

“What we know now is that we can spare most patients the need to undergo a risky and costly treatment,” said principal investigator Suresh Vedantham, MD, a professor of radiology and of surgery at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

The findings are published Dec. 7 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Between 300,000 and 600,000 people a year in the United States are diagnosed with a first episode of deep vein thrombosis and, despite standard treatment with blood thinners, roughly half will develop post-thrombotic syndrome. There is no treatment to prevent the potentially debilitating complication. However, small studies had suggested that a procedure that delivers clot-busting drugs directly into the clot may reduce the chance the syndrome will develop. The procedure is currently used as a second-line treatment to alleviate pain and swelling in people who do not improve on blood thinners.

The Acute Venous Thrombosis: Thrombus Removal with Adjunctive Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis (ATTRACT) study – a randomized controlled trial primarily funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) – was designed to determine whether performing the procedure as part of initial treatment for patients when they are first diagnosed with deep vein thrombosis would reduce the number of people who later develop the syndrome. In 2008, then-Acting Surgeon General Steven K. Galson, MD, issued a national call to action on deep vein thrombosis and specifically called for research into the benefits and risks of removing clots.

“The clinical research in deep vein thrombosis and post-thrombotic syndrome is very important to the clinical community and of interest to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute,” said Andrei Kindzelski, MD, PhD, the NHLBI program officer for the ATTRACT trial. “This landmark study, conducted at 56 clinical sites, demonstrated in an unbiased manner no benefits of catheter-directed thrombolysis as a first-line deep vein thrombosis treatment, enabling patients to avoid an unnecessary medical procedure. At the same time, ATTRACT identified a potential future research need in more targeted use of catheter-directed thrombolysis in specific patient groups.”

The study involved 692 patients, randomly assigned to receive blood thinners alone or blood thinners and the procedure. Each patient was followed for two years.

In the procedure, doctors insert a thin, flexible plastic tube through a tiny incision in the leg and navigate it through the veins using X-ray and ultrasound guidance, until it rests within the clot. They instill a drug known as tissue plasminogen activator through the tube, give it time to digest the clot and then suck out or grind up any remaining fragments using specialized catheter-mounted devices. The procedure is expensive, costing thousands of dollars, and often requires a hospital stay.

The clinical trial showed that routine use of the procedure did not reduce the chance of developing post-thrombotic syndrome. The complication developed in 157 of 336 (47 percent) people who underwent the procedure and 171 of 355 (48 percent) people who did not, a difference that is not statistically significant.

The procedure did reduce the severity of post-thrombotic syndrome, easing patients’ long-term symptoms. About 24 percent of people on blood thinners alone experienced moderate to severe pain and swelling, but only 18 percent of people who were treated with blood thinners and clot busters did so.

The procedure also alleviated pain and swelling in the early stages of the disease, when patients are often very uncomfortable.

However, the researchers noted a worrisome increase in the number of people who developed major bleeding after undergoing the procedure. While the numbers were small – one patient (0.3 percent) on standard treatment experienced a bleed, compared with six (1.7 percent) of those who received clot-busting drugs – and none of the bleeds was fatal, any increase in bleeding is a red flag. The potential for catastrophic bleeding is why powerful clot-busting drugs usually are reserved for life-threatening emergencies such as heart attacks and strokes.

“We are dealing with a very sharp double-edged sword here,” said Vedantham, who also is an interventional radiologist at the university’s Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology. “None of us was surprised to find that this treatment is riskier than blood-thinning drugs alone. To justify that extra risk, we would have had to show a dramatic improvement in long-term outcomes, and the study didn’t show that. We saw some improvement in disease severity but not enough to justify the risks for most patients.”

While the study showed that most patients should not undergo the procedure, the data hint that the benefits may outweigh the risks in some patients, such as those with exceptionally large clots.

P Clot Trial

“This is the first large, rigorous study to examine the ability of imaging-guided treatment to address post-thrombotic syndrome,” Vedantham said. “This study will advance patient care by helping many people avoid an unnecessary procedure. The findings are also interesting because there is the suggestion that at least some patients may have benefited. Sorting that out is going to be very important. The ATTRACT trial will provide crucial guidance in designing further targeted studies to determine who is most likely to benefit from this procedure as a first-line treatment.”

For now, the procedure should be reserved for use as a second-line treatment for some carefully selected patients who are experiencing particularly severe limitations of leg function from deep vein thrombosis and who are not responding to blood-thinners, Vedantham added.

P Clot Trial Meaning

The ATTRACT study was led by researchers at Washington University; McMaster University in Ontario, Canada; Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston; and St. Luke’s Mid-America Heart Institute in Kansas City, Mo.